…”Corporations have neither bodies to be punished nor souls to be condemned. They, therefore, can do as they like (Lord Chancellor Thurlow).”[1]

How did a subcontinent come to be ruled from a boardroom in London?[2]

On December 31, 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted a royal charter to over 200 English merchants who wanted to get into the East Indies spice trade.[3] England wasn’t a major European power yet and the Spanish and Portuguese empires ruled the trade.

When England defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, however, it had blown open the shipping routes used by Spanish and Portuguese traders. So the East India Company was ready to sail eastwards … but was unfortunately outdone by the burgeoning Dutch East India Company.

The Dutch went on to capture the spice trade in Indonesia. The East India Company had to settle with India.

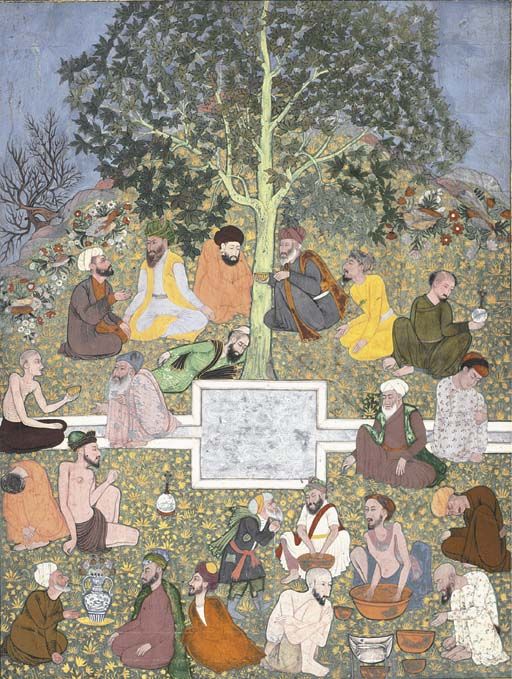

In the early seventeenth century, India was the world’s largest economy.[4] It was known for its cotton, silk and textile industries. Tales of the wealth and splendour of the Great Mughal had begun doing their rounds in England.[5]

When trying to enter India, however, the East India Company clashed with the Portuguese who had been there since 1510. The English defeated the Portuguese at the Battle of Suvali in 1612, ending Portugal’s monopoly of Indian trade.

That same year, James I dispatched an embassy to India led by Sir Thomas Roe. Roe signed a treaty with the Mughal Emperor Jahangir which let the Company set up factories in Surat in 1612.

The Company went on to set up trading posts in Madras (1639), Bombay (1664) and Calcutta (1696). It faced competition from yet another European power: the French had established trading posts and factories in the south of India.[6]

The Company’s fortunes, however, were about to change. The Mughal Empire, having expanded into the Deccan, had now grown too large to be governed effectively. The Emperor Aurangzeb’s religious intolerance had also sparked resentment and rebellion across India including among the Marathas and the Rajputs who formed the backbone of the Mughal army.

When Aurangzeb died in 1707, the once-mighty Mughal Empire, strained and divided, began to disintegrate. New regional powers like the Marathas in western India began forming their own kingdoms while others, like the Nizam of Hyderabad, declared their independence from the Mughals.

By this time, the British and French East India Companies had built their own forts and settlements in southern India and in Bengal. As Mughal India fragmented into regional kingdoms, the British and French took advantage of the political situation by playing off one Indian ruler against another.

The Indian kings were also keen to wipe one another out by accepting British and French military assistance. The Maratha prince, Balaji Baji Rao, for one, offered the Company land for batteries of artillery and trained gunners.[7] The princes of Karnataka enlisted the Company’s help which they paid for by assigning it lands and the right to collect taxes.[8]

From Company to Conquest

In Bengal, however, the British met with resistance.

Bengal was the richest, most fertile and densely populated region of India.[9] The Company had established a trading post there in Calcutta in 1696, known later as Fort William.

With the break-up of the Mughal Empire, Bengal came to be ruled by local princes (nawab in Urdu). In 1756, Siraj-ud Daula became Nawab of Bengal. Wary of the growing British presence there, he ordered his troops to seize and occupy the Company’s bases at Kasimbazar and Calcutta in 1756.[10]

The Company reacted with vengeance.

Under the leadership of Robert Clive, it quickly recaptured Calcutta on January 1, 1757, and, on June 23, 1757, it defeated Siraj’s forces at the Battle of Plassey (above). The Company’s conquest of India had begun.

The Plunder of Bengal

Between 1757 and 1763, the East India Company drained Bengal’s wealth. It forcefully taxed peasants, punished unwilling suppliers who objected to its prices and vanquished local competitors.[11] Tragically, its ruthless extraction of Bengal’s resources aggravated the Great Bengal Famine of 1770 which killed over 10 million people (roughly one-fifth of Bengal’s population).[12]

The Company meanwhile shipped bales of cotton, calico, muslin and chintz from Bengal back to Britain.[13] Its huge wealth and vast resources had made it, in the words of one of its directors, “an empire within an empire,” answerable to no one except its shareholders.[14]

Men like Clive (above) made huge fortunes in Bengal and returned to England as “nabobs” (a corruption of nawab).[15] Once back home, the nabobs bought seats in Parliament and bribed senior politicians for favours toward the Company. Parliament responded by investigating the nabobs and the Company for corruption and extortion in their dealings in Bengal. One parliamentary pamphlet decried the looting of:

“Lacks and crowes (lakhs and crores) of rupees, sacks of diamonds, Indians tortured to disclose their treasure; cities, towns and villages ransacked and destroyed, jaghires (jagirs) and province purloined. Nabobs dethroned, and murdered, have found the delights and constituted the religions of the Directors and their servants.”[16]

The Conquest of Hindustan

From Bengal, the Company marched up the Ganges into the heart of India.

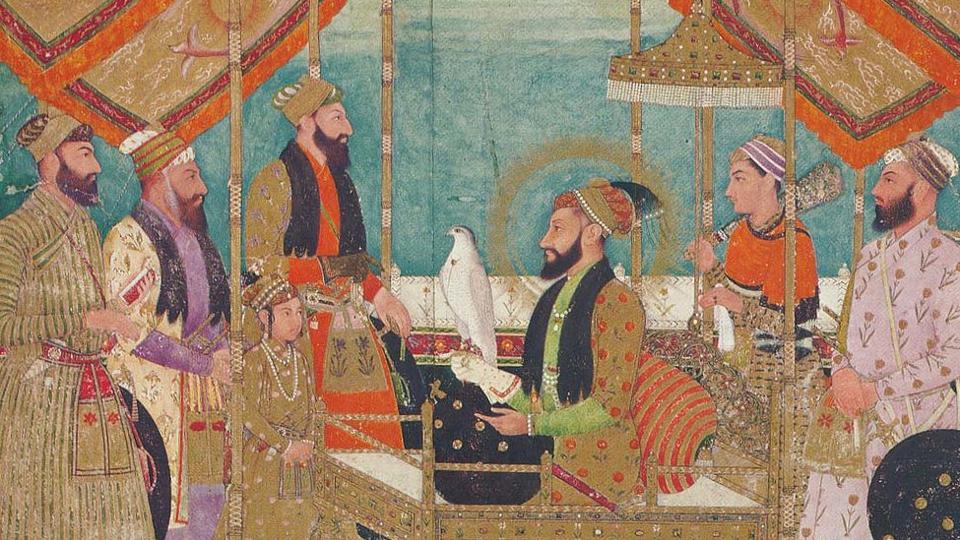

In 1764, the Company defeated the Mughal army of Shah Alam II at the Battle of Buxar. The Treaty of Allahabad of 1765 (pictured at the top of the page) brought Awadh under Company control and won it the diwani or right to collect taxes on behalf of the Mughal emperor.

In less than a century, the Company swooped across the south through conquest and by granting suzerainty to local rulers such as the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1747. Having annexed the Punjab in 1849 (after defeating the Sikhs in the Second Anglo-Sikh War), the Company had brought Hindustan to heel.

By 1857, India was ruled from a boardroom in the City of London.

The Company laid the foundation for British rule of the subcontinent. The historians of the British Raj, however, would see the Company as a national embarrassment. By the 19th century, Victorian Britain had begun to see the British nation (and not a predatory corporation) as the builder of destiny and the shaper of progress. The Company became in the eyes of many a “tyranny which [had] encouraged and exploited human suffering.”

The East India Company was the world’s first truly multinational corporation. Its plunder of India should serve as a warning to a world ruled by Walmart, Apple, BP and Wells Fargo.

Sources

The Anarchy: A New Book by William Dalrymple: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUeyOEY9oWg

BBC Start the Week (Dec. 2, 2019): https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000bvw5

British Library (East India Company): https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item102770.html

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Bloomsbury Publishing: 2019 [Audiobook]).

William Dalrymple, “The East India Company: The original corporate raiders,” The Guardian, March 4, 2015: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders

Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (St. Martin’s, New York: 1997).

Ben Johnson, “The East India Company and its role in ruling India,” Historic UK: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-East-India-Company/

Andrea Major, “The East India Company: How a trading corporation became an imperial ruler,” HistoryExtra: https://www.historyextra.com/period/tudor/the-east-india-company-how-a-trading-corporation-became-an-imperial-ruler/

Amartya Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. (Oxford University Press: 1982). Available online: https://www.prismaweb.org/nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Poverty-and-famines%E2%94%82Amartya-Sen%E2%94%821981.pdf

Notes

[1] William Dalrymple: The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUeyOEY9oWg). This was Lord Chancellor Thurlow speaking at the impeachment trial of Warren Hastings.

[2] I was inspired to write this blog after listening to a BBC Podcast on William Dalrymple’s latest book on Indian history, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company.

[3] William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Bloomsbury Publishing: 2019), Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 (audiobook). The royal charter was granted after a Dutch delegation arrived in England offering to buy out all English ships which were intended to voyage to the East. This infuriated the English merchants who petitioned the Privy Council to reject the proposal for the “honour of [their] native country.” The charter also authorized the East India Company to wage war, raise forts and make settlements in any new territory to which they voyaged.

https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item102770.html. The “East Indies” here refers to Asia.

[4] BBC Start the Week (Dec. 2, 2019): https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000bvw5. Dalrymple estimates that India generated roughly 30% of the world’s GDP at the time.

[5] A Handbook for India: Being an account of the Three Presidencies and of the Overland Route (London: John Murray), 1859, lxxx. In 1603, the English Jesuit priest and missionary, Thomas Stephens, visited the Mughal capital of Agra, returning to England with stories of the wealth of the Great Mughal.

[6] The French established a factory at Masulipatam (Andhra Pradesh) in 1669, acquired the area of Pondicherry in 1673.

[7] Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (St. Martin’s, New York: 1997), 10.

[8] James, 9.

[9] James, 30.

[10] On the night of June 20, 1756 (in what came to be known as the “Black Hole of Calcutta”) Siraj’s forces herded an unknown number of British prisoners into a small cell in the dungeon of Fort William where over half of the prisoners suffocated to death.

[11] James, 38-39.

[12] Amartya Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. (Oxford University Press: 1982), 39.

[13] James, 10.

[14] James, 49.

[15] Dalrymple estimates that Clive returned to Britain with a personal fortune valued then at £234,000 (around £23 million in today’s currency) making him the richest self-made man in Europe.

[16] James, 49. The pamphlet dates to 1773. Parliament’s investigations reached their climax between 1788 and 1795 with the trial to impeach the Governor of Bengal (Warren Hastings) for looting and corruption. Hastings was acquitted.