Histories of Indian literature often neglect, if not completely overlook, the contribution of Persian to Indian literature. Given that Persian was the language of literature for over eight centuries in India and, given the ongoing Hindu Nationalizing of India’s history, an understanding of the history of Indo-Persian literature is more necessary than ever.

THE TURKISH CONQUEST

The north-west of India has been subject to invasions since ancient times. Beginning in the second millennium BCE until the 10th century, north-west India experienced invasions at the hands of Aryans, Iranians, Greeks, Parthians, Scythians, Kushans and Huns.

In 962, Alptigin (901-963), a Turkic general in the Samanid Empire (819-999) abandoned the court at Bukhara and established a semi-independent state with its capital in Ghazni (present-day Afghanistan).[1] He was succeeded by his son, Abu Mansur Sabuktigin (942-997), who in 986 launched an attack on Kabul and Punjab. Sabuktigin died in Balkh in 997 and was succeeded by his son Mahmud (971-1030).[2]

Between 1001 and 1017, Mahmud launched a series of raids into northern India from Ghazni. In 1008, he conquered and annexed Punjab. By the time of his death in 1030, his empire spanned Khorasan, Samarkand, Afghanistan and Punjab.

EARLY INDO-PERSIAN LITERATURE

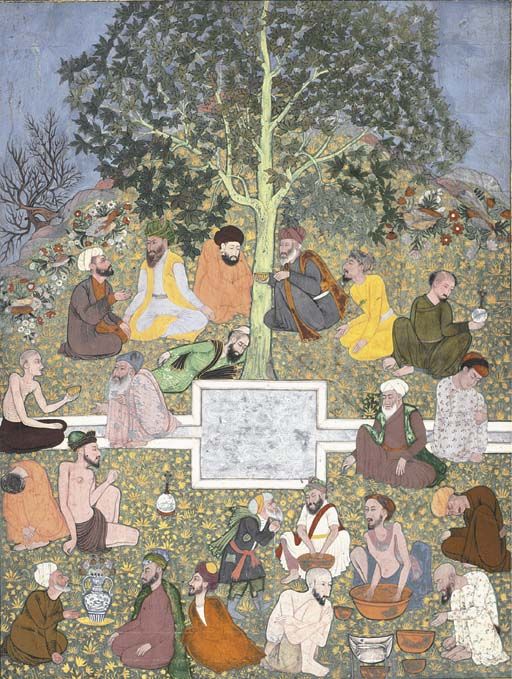

The Turkish conquest of north-western coincided with what the British historian E.G. Browne has called the “Persian Renaissance.”[1] Beginning under the Samanid Empire in Bukhara, which saw the completion of the Shahnama (‘Book of Kings’), Persian literature flourished in courts across Central Asia and Iran.

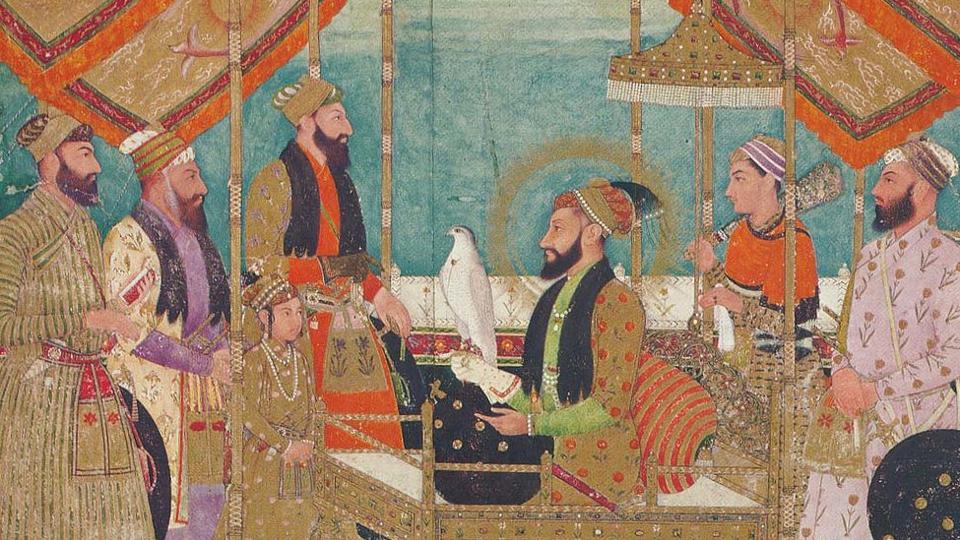

Mahmud’s court at Ghazni became a centre of Persian literature. Mahmud brought scholars, merchants, artists and Sufis with new ideas in art, architecture, literature and religion to India. Mahmud’s court attracted the scholar Al-Biruni (whose work on the history of India included an assessment of scientific works in Sanskrit and Hindu philosophies and religion) and Firdowsi, author of the Persian epic, Shahnama.

The Ghaznavid Empire in Khorasan was repeatedly invaded by the Seljuq Turks until it was lost in 1040. In 1163, the Ghaznavid Sultans moved their capital from Ghazni to Lahore where they would rule from until 1186.

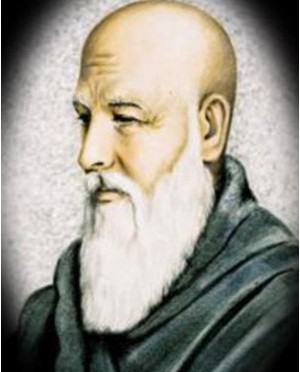

It was in Lahore where the first Indo-Persian literature appeared. ‘Ali Hujviri’s (d. 1071) Kashf-ul Mahjub (‘Veiling the Unveiled’) was the first Persian treatise on Sufism. It set out such themes as the love of God, the importance of contemplation and the stages of the mystical path:

Man’s love toward God is a quality which manifests itself in the heart of the pious believer, in the form of veneration and magnification, so that he seeks to satisfy his Beloved and becomes impatient and restless in his for vision of Him, and cannot rest with anyone except Him, and grows familiar with the remembrance of Him, and abjures the remembrance of everything besides.[2]

Early Indo-Persian poets like Abu al-Faraj (d. c. 1102) continued the Persian tradition of panegyric poetry (qasida) at court as well as the Persian poetic tradition of contrasting metaphors such as moth and flame, rose and nightingale and lover and beloved.

MAS’UD SA’D SALMAN (1046-1121)

Mas’ud Sa’d Salman’s poetry was especially important to the development of early Indo-Persian poetry. While Mas’ud continued to write in the tradition of Persian court poetry, his verse also showed openness and sensitivity to the new Indian poetic landscape.

Born in Lahore, Mas’ud was of Iranian ancestry. His father, Sa’di Salman, had come to Lahore as an accountant in the entourage of Prince Majdud who had been sent by Sultan Mahmud to garrison Lahore in 1035-36.[3]

Mas’ud spent much of his professional life as a poet between the courts of his patrons and in prison for reasons which are not clear. It was in prison, however, that he pioneered the habsiyat (prison) genre of poetry, a genre that would appear in the later Urdu poetry of Ghalib and Faiz Ahmad Faiz.[4]

Mas’ud often wrote on the pain of his separation from his beloved city of Lahore:

O Ravi, if paradise is to be found, it is you,

If there is a kingdom fully equipped, it is you

Water in which is the lofty heaven is you

A Spring in which there are a thousand rivers is you.[5]

He also introduced the Indian genre of the baramasa to Indo-Persian poetry:

O beauty whose arrows are aloft on the day of Tir

Rise and give me wine with a high melody

Sing of love in the mode of love

Call forth the delightful melodies of nature[6]

THE GHURID INVASION

In 1186, Lahore was conquered by Muhammad of Ghur, one of vassals of the Ghaznavid Empire. Like the Ghaznavid Empire, the Ghurid Sultanate encompassed much of Central Asia, Iran and northern India. In 1192, Muhammad defeated Prithviraj Chauhan at Tarain (present-day Haryana) from where he conquered the political centres of north India.

THE FOUNDING OF THE DELHI SULTANATE

In 1192, Muhammad of Ghur ordered his Turkic slave, Qutb al-Din Aibek (1150-1210), to push further east.[7] This resulted in the conquest of Delhi which, along with Lahore, Muhammad placed under Aibek’s governorship.

In 1206, Muhammad was assassinated. A civil war broke out between his slave commanders with Aibek emerging the victor.[8] Aibek established his own empire with Delhi as his capital, thus founding the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526).

… to be continued.

NOTES

[1] Richard Eaton, India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765 (University of California Press: Oakland, CA: 2019, 13), 30.

[2] Ibid., 30.

[3] Sunil Sharma, Persian Poetry at the Indian Frontier (Permanent Black: New Delhi, 2010), 19.

[4] Annemarie Schimmel, Islamic Literatures of India (Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 1973), 11: https://archive.org/details/IslamicLiteraturesOfIndia-AnnemarieSchimmel/page/n3/mode/2up

[5] Sunil Sharma, Persian Poetry at the Indian Frontier, citing Diwan, 391.

[6] Sunil Sharma, Persian Poetry at the Indian Frontier, citing Diwan, 947-8.

[7] Richard Eaton, India in the Persianate Age, 42.

[8] Ibid., 44.

Urdu ebook

Urdu ebook